5. Explore the World and Broaden Your Horizons

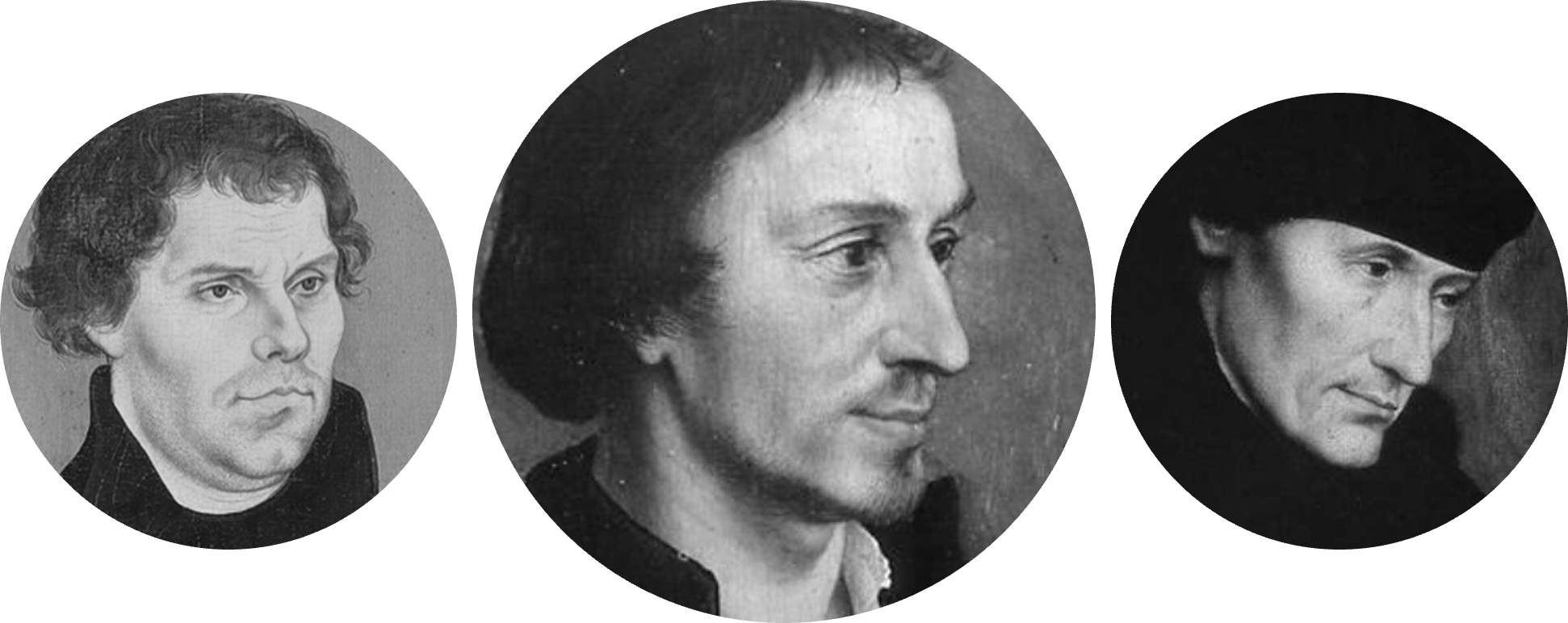

A Wise Reformer Leads the Way

The Renaissance humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam was a champion of classical education. He understood that man is full of faults, but he had hope that he could improve. Through grace he could become God’s co-creator. He praised compassion, humility and moderation. ”Your library is your paradise,” he said.

Martin Luther’s friend and colleague Philipp Melanchthon followed the same line. He too recognised the importance of education. ”Melanchthon’s great and lasting achievement is to have reconciled the Reformation with the classical educational heritage and in this spirit to have laid the foundations of the Protestant school of learning.”

Following Melanchthon's example is a very good idea. Faith and classical Bildung make a good combination.

A Precious Treasure

A good place to start is with the ancient Greeks. There are those who reject ancient Greek democracy because it excluded women and slaves. Certainly there was no small amount of elitism, sexism, racism and fascism in the ancient world. Neither the people of the Bible nor the classical philosophers were free from such things.

But the dark background need not discourage us. It is precisely the liberation from the might-is-right philosophy that is important. Both successes and failures can be relevant to us.

Since these people lived in a completely different culture, we can try to see ”similarities between different things and differences between similar things”. In this way we can search for the principles that underlie the art of being human.

The accumulated experience of humanity is a precious treasure, and to forget it is not very progressive. To move forward, we must learn from history.

To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child, said Cicero.

Athens and Sparta

It is quite impressive that ancient Athens had a system of government that was as inclusive as it actually was. They developed a democracy that did not rely on bureaucrats and professional politicians. Instead, they relied on the participation of citizens and their ability to use their common sense.

Athens was at odds with Sparta, which practised a much more brutal form of slavery. They could not understand why Athens gave power to the uneducated masses. Instead, their system of government was an oligarchy, the rule of the few.

The Spartans worshipped the god Phobos (fear) for his ability to create discipline and uniformity. Their society was marked by extreme collectivism and their culture was – Spartan. The Athenians also had their follies, but they had a rich and flourishing culture.

Which Form of Government Is Best?

Athens and Sparta represented two contrasting political ideals and clashed for influence among the Greek city-states. These two ideas that are still in conflict.

The first idea is that all citizens are basically equal and should have a say in the affairs of society. Everyone has common sense, and if they don’t, they can develop it over time through engagement in society and equal dialogue. If people are treated as adults, it is possible that they will actually become adults.

The second idea is that people are not equal. Humanity can be divided into ”the clever and enlightened” and ”the stupid and unenlightened”. To create a good society, the former must have power over the latter.

Plato lived in Athens, but he followed the second line. He wanted to introduce aristocracy – ”the rule of the best”, that is, rule by a noble and cultured elite. He was highly critical of democracy, which he believed gave free rein to passions and irrationality. Sooner or later, he argued, it would degenerate into tyranny.

The great challenge for democracy in our time is to prove Plato wrong on this point.

We should remember, however, that what we now call democracy is more a legacy of ancient Rome than of Athens. Cicero lived in the Roman Republic, which had a kind of mixed form of government: monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. The rule of one leader can create capacity for action. Rule by the wisest can provide expertise. Rule by the common people can promote common sense. Cicero believed that a well-designed constitution takes the best from each.

In Chapter 8 of my book Adventures and Reflections, I describe my work on water supply in Nepal during the Maoist insurgency. There I argue for Karl Popper’s idea of the open society. Popper is known for his harsh criticism of Plato. Too harsh, I think. Even those of us who believe in democracy can learn from Plato’s ideas. You can read Chapter 8 further down the page.

Who Can Think Freely?

The Swedish philosopher and educator Alf Ahlberg believed that a functioning democracy requires us to develop the ability to think freely. The problem is not a lack of freedom of expression, but our tendency to enslave ourselves.

Ahlberg argued that we humans are very good at convincing ourselves that we are more rational than we really are. We defend our opinions with reasons that seem logical but are really based on desires, sympathies and antipathies. We see facts that flatter and please us, and turn a blind eye to what humiliates and angers us. We easily fall prey to social prejudices and superstitions. He wrote:

In our narcissistic culture, free thinking is synonymous with following your innermost feelings. Freedom means inflating your ego and giving it free rein. Your subjective opinion becomes something sacred that should not be violated. True is what feels right. Good is what feels good.

Socrates was adamant that these are not the same thing. Such subjectivism makes us easy prey for those who are skilled at manipulating emotions.

Ahlberg argued that fascism and other totalitarian ideologies are based on primitive subjectivism. Collective feelings of flattery, hatred and revenge are believed to be good because they are pleasurable.

Those who like to hate are unfree and easy to control. Clever demagogues can easily make them dance to their tune by pushing the right buttons.

Out Of the Dark Shadowlands

Plato can be a friend in need. In The Republic, he admittedly put forward some undemocratic and rather absurd ideas. It was shocking to his contemporaries in Athens that he used the collectivism of Sparta as a model. His student Aristotle thought he went too far.

At the same time, The Republic can be surprisingly progressive. Socrates described an ideal society ruled by educated and noble leaders. Plato’s own brother Glaucon listened and was deeply impressed:

– Ruling women too, Glaucon! I replied. You must not think that what I have said applies more to men than to women …

Wise women must be educated to rule society as philosopher-queens, thought the feminist Plato. In Athens in 400 BC, this was a revolutionary idea. Unfortunately, no one took it up.

There are both good and bad political ideas in The Republic. But what is perhaps most relevant to us today is not its politics, but its psychology and virtue ethics.

Plato divided the soul into three parts. The first is reason and the second is desires and drives. The third can be described by words such as combativeness, ambition, passion and spiritedness.

Chaos arises when, for example, desire begins to rule over reason. Or when the urge for action becomes an unbridled desire for power. Plato argued that there must be no internal civil war between the three parts. He wrote:

Inner health is about the creation of inner harmony. According to Plato, the three parts of the soul (reason, will and desire) must be coordinated so that each has its proper place and function.

A disorganised soul, he believed, was bound by its desires and fixations. It is like being chained up in a dark cave, lost in shadows and illusions. ‘The Form of the Good’ is like the sun that makes everything appear in its proper light.

The way out of the cave, according to Plato, is through education and virtue. He reflected on what would later be called the four cardinal virtues. Today we could interpret them in the following way:

-

Wisdom, e.g. knowing what you don’t know.

-

Justice, e.g. fair-mindedness.

-

Moderation, e.g. not going to extremes.

-

Courage, e.g. not letting fear rule over reason.

Can a democracy function well without the Platonic cardinal virtues?

6. Develop a Healthy Inner Strength

A Tried and Tested Philosophy of Life

The ideas of the Greeks were passed on to the Romans, who developed a philosophy called Stoicism. It is relevant to those who want to be grounded in reality and work for the common good. Stoic philosophy contains some ideas that belong to an outdated worldview, but also things that are timeless.

It is in many ways embedded in Christianity. Many of the Christian church fathers, and probably St Paul, were influenced by the Stoics. Luther, Melanchthon and Erasmus had one thing in common: all three liked the writings of Cicero, which contain many Stoic ideas.

Alf Ahlberg wrote: ”The humanist tradition is based above all on a fusion of Stoicism and Christianity”. He argued that the Western humanist tradition has been shaped by a number of religions, philosophies and epochs. It developed during the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Enlightenment. Its ancient roots lie in Judaism, Christianity, Greek philosophy and Stoicism. He wrote that this is ”the great line of our culture, on whose existence and vitality its whole future depends”.

The synthesis of Stoicism and Christianity is the origin of a precious treasure: the belief in human rights. This idea has matured and developed throughout history. This was mainly done by Cicero in antiquity, and then by Christian philosophers such as Thomas Aquinas in the Middle Ages, and Locke and Kant in the Enlightenment.

There are times when the West seems to have completely lost its moral compass. That is when we need to reconnect with our historical and spiritual roots.

Not callousness!

A common misconception is that stoicism must lead to an emotionless and cold state of mind. It is true that it can be exaggerated, but what it is really about is self-awareness and self-control.

It’s not a matter of suppressing emotions, it’s a matter of getting to know them, accepting them and dealing with them. Too much stoicism is harmful, but in moderation it is healthy. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a modern successor to stoicism.

Training the Soul

The ancient Stoics were inspired by the philosophy of Socrates, which included the idea that it is better to suffer wrong than to do wrong. They saw him as an example of how to live in a stormy world with inner peace and without corrupting one’s soul.

The Stoics believed that man’s most precious possession was the integrity of the soul. This means that external things such as success and wealth are less valuable. This can be compared with Jesus’ statement: ”What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world but loses his soul?”

The Stoic Epictetus saw God as a primal force that creates an inner strength in the soul. The Serenity Prayer is rooted in his philosophy.

Most of what happens in the world is beyond our control, but what we can control are our reactions, said Epictetus. We can control are our opinions, desires and aversions.

For a Stoic, it is important to maintain an inner peace of mind that is independent of external circumstances. You must not allow yourself to be enslaved by base thoughts.

”We have nothing to fear but fear itself”, said Franklin D. Roosevelt. The ability to feel fear is, of course, absolutely vital. We live in a dangerous world and if we couldn’t feel fear, we would put ourselves in dangerous situations unnecessarily. What Roosevelt warned against is a fear that impairs judgement. Dangers and threats must be assessed with a balanced mind that neither overreacts nor cowardly closes its eyes to reality.

Fear can lead to anger and hatred, Yoda said. There are many people today who live in a state of almost chronic anger. They do not realise that they are corrupting their intellect.

- Fear can create delusions.

- Anger can create tunnel vision.

- Hatred can create blindness.

Courage is keeping a cool head in order to see more clearly.

This virtue can only be developed through practice. You have to face things that are frightening. The trials of everyday life can become exercises in keeping one’s balance. Epictetus gave the following advice to someone visiting a bathhouse (in the Roman Empire around 100 AD):

According to Stoicism, it is important to be able to think negatively and try to imagine unpleasant surprises. This may sound like pessimism, but it is actually optimism. It’s like saying to yourself: ”Even if I encounter difficulties and setbacks, I have an inner readiness to deal with the problems”.

For a Stoic, it is particularly important to reflect on one’s mortality and to be grateful for the life one has. This puts the world into a truer perspective.

It is important, however, that these Stoic exercises are not overdone. It should not lead to emotional coldness, indifference and an inability to care.

Feelings of frustration and anger can be important motivators. The main thing is that anger does not become a pleasure and an unrestrained habit.

Power Does Not Always Corrupt

It is often said that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. However, it seems that there is one exception and that is the emperor and stoic Marcus Aurelius. He had unlimited power to do whatever he wanted, but he tried hard to resist the temptation.

A Stoic sets limits to himself and his actions – not everything that can be done should be done – and has enough self-discipline to respect those limits. Power does not provide freedom from the burden of following principles.

”Beware of being a tyrant,” Marcus said to himself. ”So be honest, good and upright, love justice, be pious, be kind and loving, and be steadfast in the discharge of duty.”

Those who have power over others must first have self-awareness and self-control. This philosophy of life is relevant to politicians, civil servants, police officers, managers and others whose duty it is to serve a higher ethic and the common good.

Justice And Fair-Mindedness

Why be honest if it is more profitable to be corrupt? This was Glaucon’s challenging question in The Republic. Socrates’ answer was illuminating. A healthy body has value in itself. The same is true of the soul. The soul of the unjust is sick, while the soul of the just is healthy. Inner health has an intrinsic value, even if it is not always ”profitable”.

Justice is the defence against the idea that might is right. There are those who say they are fighting for justice, when in fact they are fighting for power and revenge. This is what happens when one lacks inner justice. The struggle for justice is both an inner and an outer struggle.

Anger can be the driving force for justice – but not hatred. It is important to set limits for oneself and to learn not to cross those limits.

Marcus Aurelius

The Christian Hope

The Christian belief in life after death can lead to a pious escape from the world, but it doesn’t have to be that way. On the contrary, it can become a source of inner strength. Hope protects us from emptiness and cynicism.

Heavenly hope gives the feeling of having a home. It creates a natural stoicism that is not forced or contrived. Even if everything goes wrong, all is not lost. Hope becomes an inner source, which is less dependent on circumstances.

The heavenly hope can therefore also create an earthly hope. Bonhoeffer wrote:

7. Develop the Capacity to Integrate

The Challenge of Cultural Diversity

How can people from different cultures live together in harmony? What should they do when they are strangers to each other and have very little in common with each other? Should they strive for unity or diversity? Do they want to live in equality, or does one group try to dominate? This leaves four possibilities.

1. Mosaic: Equality and Diversity. In a mosaic, people from different cultures live side by side. They stick to their own traditions and do not change their language or ways of living and thinking. No one culture is considered superior to another. However, the harmony is easily disturbed and there is a constant fear of domination. In this situation you have to be politically correct and walk on eggshells so as not to offend anyone. Everything is linked to identity, pride and inferiority complex. The danger is that people get on each other’s nerves.

2. Segregation: Dominance and Diversity. In a segregated society, some groups of people float on top. It’s like oil and water: they never mix, no matter how much you stir. An example of this is South Africa and Namibia under apartheid. Some people believe that it is a divine order that some people should have power and privilege. If others just submit, they can be accepted like children in a family. Social harmony, they say, should be based on submissive respect and patriarchal benevolence.

3. Melting pot: Equality and Unity. A melting pot is created when all communities cut the roots of their respective traditions and see only what they have in common. It can easily absorb ideas and impressions from all corners of the world. It develops a cosmopolitan culture characterised by easily consumed food, art and music. The melting pot becomes fluid and unhistorical, shunning anything complicated. Those who cling to their traditions are seen as abnormal.

4. Homogenisation: Dominance and Unity. People in a homogeneous group tend to think that what is common must be normal. And what is normal must be natural. And what is natural is probably a divinely ordained order. All deviant elements must be eliminated or transformed. Here it becomes admirable to be politically incorrect, and those who pick on minorities are seen as tough and strong. The most brutal forms of homogenisation are ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Moderation And Balance

Which of these strategies should we choose? Notice that they all have one thing in common. They are different ways of avoiding what is foreign and different. The hope is to eventually reach a state of harmony, free from friction. But the result is often just the opposite.

To solve these problems we need to develop what is known as Cultural Intelligence (CQ).

First, we need to learn how to deal with pride in our nation, tradition, uniqueness, identity, etc. Pride is like drinking wine: one or two glasses is pleasant and increases self-confidence, after three or four glasses you lose your judgement and say stupid things, after five glasses you become aggressive. Everything in moderation.

We must also recognise that political correctness and political incorrectness are two extremes to be avoided. Respect without honesty easily leads to hypocrisy. Honesty without respect easily leads to bullying.

A well-integrated person can hold two thoughts in his mind at the same time. It is possible to be both truthful and considerate.

The ability to solve this round square is essential for those who really want to communicate and be understood.

Avoid Stubborn Dogmatism and Lazy Relativism

Dogmatists cannot be wrong. But neither can relativists, because in their minds there is no right or wrong. Both are unwilling to listen to counter-arguments. Neither understands that they are trapped in their intellectual fixations.

Socrates was able to engage people and encourage better thoughts and ideas. Know thyself! he said. Be aware of your own ignorance! Only then can we free ourselves from delusions. To become wiser, we must help each other through dialogue.

This was not a dialogue between deaf people, where no one listens to the other’s arguments. If the person who disagrees with me is right, I am the first to give in, Socrates said. He said, ”Wherever the winds of discussion blow – there we must go”.

It is this kind of give and take dialogue that can provide the Platonic insight: truth is something that can be approached and that in some sense exists.

”I have the absolute Truth,” says the dogmatist. ”Your truth is not my truth,” says the relativist. Neither seeks truth through dialogue with others. Trapped in their shells, they cannot change, grow and evolve.

But suppose there is an objective Truth that stands above our favourite private ideas. Then the possibility opens up that our opinions need to be corrected. Being guided by the Truth keeps us awake from both dogmatic and relativistic slumber.

λόγος (Logos)

Another name for Christ is Logos. It is Greek and can be interpreted as ”the organising principle of existence”. Those who wish to follow Logos must live by one important rule: never call another person a fool.

The just man respects his opponents and focuses on the issue rather than the person. It is better to use arguments than to manipulate emotions.

Following Logos is an adventure. Those who do so can make an important contribution to our troubled world: spreading the art of dialogue and reasoning.

8. Develop Practical Wisdom

Technocracy Undermines Aid to Poor Countries

In my book Adventures and Reflections, I talk about my work as a water and sanitation engineer in poor countries. In my view, aid is characterised by too much social engineering. This means that beneficiaries have little opportunity to think and act independently.

This criticism has been made by many in different contexts. Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah, for example, writes that aid has become mired in bureaucracy and technocratic control. Too much time and energy is spent on reporting. This leads to the temptation to design projects so that they are easy to measure.

He argues that we need to turn this around and see civil society as a deeply human activity that fosters social relationships. ”It is these relationships, history teaches us, that can truly change the world.” he writes.

If we really want to help people out of poverty, we should support local organisations that focus on practical problem-solving and only occasionally seek outside help. Women and men organising themselves to solve everyday problems is what aid should support.

Do Not Misuse the Noble Science!

A mindless pursuit of results can be very damaging to a culture of cooperation. Practical wisdom, patience, self-confidence, responsibility, willingness to compromise – these hard-to-measure qualities can be undermined when quick and measurable results are demanded. Quality must take precedence over quantity.

Some people are convinced that everything in life can be measured mathematically. They are probably right. But the essential question, of course, is whether it makes sense to measure everything. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote:

Mathematics is a fantastic tool, but using it wisely requires good judgement.

Mindless measurement is something that pervades much of our modern society, argues philosopher Jonna Bornemark in The Renaissance of the Unmeasurable – A Challenge to the Hegemony of Pedants. She writes:

This is something that drastically reduces the space for experienced people to use their own judgement, she says.

It is bad enough that our society is characterised by this harmful way of thinking. But why spread it to poor countries?

What we need today are people who work for aid that is guided by quality thinking. This means, for example

- Valuing the long-term more than quick results.

- Promoting a culture of co-operation.

- Training women and men to be wise and just leaders.

φρόνησις (Phronesis)

An important key to better aid is what Aristotle called phronesis, which can be translated as practical wisdom, common sense and good judgement. This is something that is developed through work and life experience and through education.

It is an intuitive form of knowledge that involves being able to discern what is essential and what is non-essential in any situation. It means being able to consider different courses of action in order to choose the best one.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle tried to work out how we can cultivate our emotions so that they are in harmony with good judgement. Virtue, he argued, is about creating good habits. Phronesis is related to moderation. In practical life, we often need to find the golden mean and not go too far in either direction. In decision-making situations, it is important to neither overreact nor underreact, he said.

The Shortcomings of Technocracy

Aristotle distinguished phronesis from techne, or technical knowledge. This form of knowledge is also needed, of course, but if aid becomes a technocracy without phronesis, it will almost always do the wrong things.

Experts are indispensable because they are knowledgeable in a particular field. At the same time, they are inherently more ignorant of what lies outside that area. Like all human beings, they are limited.

But what if they lack knowledge of something important, namely knowledge of their ignorance? What if they have a weak and diffuse understanding of their limitations? If they lack self-awareness, they tend to overestimate themselves and make confident statements about things they do not understand. Since the domain of competence is like a small island in a large ocean, it is likely that they are often in uncharted waters without realising it.

It was this kind of ”half-education” that Socrates thought he saw in the technicians and engineers of his time. He noticed that although they were very knowledgeable in their field ...

A technocracy is a government of ”half-educated” experts. Being an expert in one area can create a false sense of being an expert in everything.

Bildung Has Practical Importance

Gaps in knowledge are often filled with ill-considered answers. This is the result of ”blind ignorance”. Classical education (Bildung) can create a kind of ”enlightened ignorance” and a better understanding of what one does not know.

”Being able to hold cultured conversations or quote the classics is not a classical education,” writes Lars Dencik. He continues:

If we lack good judgement, we cannot deal with environmental problems or any other problem. Both rich and poor countries need educated leaders who can combine expertise with good judgement.

Such people may not always have the right answers, but they are often good at solving problems through dialogue.

This ability can be developed by getting to know the different dimensions of life. This can include, for example:

- Nature and culture

- Humanities and technology

- Tradition and progress

- Quantity and quality

- Facts and values

Kindle ebook

Paperback

Texts by Erik Pleijel, published on this website, are licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Cartoon boy: VectorStock; Tecknad drottning, sengångare: FriendlyStock; Cartoon priest: Copyright Brad Fitzpatrick; Aristotle Kaio hfd CC BY-SA 3.0;

Luther, Melanchthon, Erasmus, School in Athens, Cicero, Marcus Aurelius, Andromeda galaxy, ospreys: Public Domain according to Wikipedia; Other illustrations: CC0 Erik Pleijel.